Crypto

Small P Problems

My buddies Whitfield and Martin were trying to share a secret key between themselves, and I was able to eavesdrop on their conversation. I bet I could probably figure out their shared secret with a little math…

p = 69691 g = 1001 A = 17016 B = 47643

The first hint is given by the subjects’ names: Whitfield and Martin are indeed Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman.

We have p and g (the modulus and the generator of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol) and we also have A and B, which are:

where a and b are two random secret numbers.

The shared secret is calculated as follows:

\[s \equiv g^{(a*b)} \equiv A^b \equiv B^a \pmod{p}\]Our goal is to find a such that $g^{\large a} \pmod{p} = A$ (or b such that $g^{\large b} \pmod{p} = B$) — mathematically speaking, we have to solve the discrete logarithm problem.

Once a is found, calculating s is trivial.

In this context we have a very small p (hence the name of the challenge!), so we can find a via a bruteforce attack with very little effort.

p = 69691

g = 1001

A = 17016

B = 47643

a = 1

guess = None

while guess != A:

a += 1

guess = pow(g, a, p)

s = pow(B, a, p)

print(s)

Wrapping the number we have our flag!

🏁 utflag{53919}

Illegal Prime

The NSA published the ciphertext from a one-time-pad. Since breaking one-time-pad is so easy, I did it for you.

To avoid legal trouble I can’t tell you the key. On an unrelated note I found this really cool prime number.

We are given a text file with the following content:

c = 2f7f63b5e27343dcf750bf83fb4893fe3b20a87e81e6fb62c33d30

p = 56594044391339477686029513026021974392498922525513994709310909529135745009448534622250639333011770158535778535848522177601610597930145120019374953248865595853915254057748042248348224821499113613633807994411737092129239655022633988633736058693251230631716531822464530907151

We can presume that c is the ciphertext, and p is the prime number.

The link in the prompt refers to the Wikipedia page about illegal primes, prime numbers that are considered illegal in some jurisdictions because they are the numeric representation of some piece of illegal software.

So if we try and interpret the number p as a byte array, it is indeed the numeric representation of the (padded) string k = 5a0b05... which really looks like our key!

Now we can easily decrypt the ciphertext as follows:

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes

c = bytes.fromhex('2f7f63b5e27343dcf750bf83fb4893fe3b20a87e81e6fb62c33d30')

p = 56594044391339477686029513026021974392498922525513994709310909529135745009448534622250639333011770158535778535848522177601610597930145120019374953248865595853915254057748042248348224821499113613633807994411737092129239655022633988633736058693251230631716531822464530907151

k = bytes.fromhex(long_to_bytes(p).decode('ascii').strip('\x00\x0f').split(' = ')[1])

plain = ''

for i, encrypted_char in enumerate(c):

plain += chr(encrypted_char ^ k[i])

print(plain)

And here’s our flag!

🏁 utflag{pr1m3_cr1m3s____!!!}

Prove No Knowledge

I’ve been trying to authenticate to this service, but I’m lacking enough information.

nc crypto.utctf.live 4354

Upon connection, we are greeted by an authentication system that will let us pass only after authenticating for 256 rounds.

Given only 3 numbers g, p and y, to authenticate one must prove knowledge of x such that $g^x \equiv y \pmod{p}$.

Each round we pick an r, send $g^{\large r} \pmod{p}$ and then send either r or (x+r) mod (p-1). Since the starting values, for some mysterious reason, never change, we only need to figure out the answer to both question once and send the same right answers repeatedly.

Before diving into the math, looking up the name of the challenge revealed that this is a well-known authentication method, known as Zero Knowledge Proof.

ZKP it’s a challenge and response method to prove knowledge of information without revealing it, based on probability. There are two possible question, one where the answer is trivially easy and therefore always known, and the other one is known only if in possess of the secret. Asking this questions randomly multiple times reduces the probability of a cheating Peggy. The typical practical example is through the use of discrete logarithms.

Peggy knows a value x and wants to prove it to Victor without revealing it.

1) Peggy randomly pick r in the range of the group and send $C = g^r \pmod{p}$

2) Victor ask one of two questions:

2.a) To send r and this could be simply verified

2.b) To send $(x+r)\bmod{(p-1)}$ and verifying as follows:

\[(C\cdot y)\ {\bmod\ p} \equiv g^{(x+r)\ {\bmod\ {(p-1)}}}\ {\bmod\ p}\]Summing up, we the verifiers, should not be in control of r.

“Not at all, Roy”, crafting $C = (g^{x})^{-1}$:

\[\displaylines{ \begin{align} (C \cdot y) \equiv g^{(x+r)\ {\bmod\ {(p-1)}}} {\pmod{p}} \\ ((g^{x})^{-1} \cdot (g^{x})) \equiv g^{(x+r)\ {\bmod\ {(p-1)}}} {\pmod{p}} \\ 1 \equiv g^{(x+r)\ {\bmod\ {(p-1)}}} {\pmod{p}} \end{align} }\]and when asked for $(x+r)\ {\bmod {(p-1)}}$ , sending 0 will do the trick.

from pwn import *

def round(v):

conn.recvline()

conn.sendline(str(v))

conn = remote('crypto.utctf.live', 4354)

conn.recvuntil('g: ', drop=True)

g = int(conn.recvline())

conn.recvuntil('p: ', drop=True)

p = int(conn.recvline())

conn.recvuntil('y: ', drop=True)

y = int(conn.recvline())

r = 1

g_r = pow(g,r,p)

modinv_gr = pow(y,-1,p) * g_r

for i in range(1, 256, 2):

round(g_r) # send g^r

round(r) # send r

round(modinv_gr) # send g^r

round(r) # send (x+r) mod (p-1)

print(conn.recvline())

print(conn.recvline())

conn.close()

🏁 utflag{questions_not_random}

A Bit Weird

I found this weird RSA looking thing somewhere. Can you break it for me? I managed to find x for you, but I don’t know how to solve it without d…

This challenge was solved after the end of the ctf

Looking at the source, there’s not much going on. This could ether mean easy peasy or dizy hard.

from Crypto.Util import number

from secret import flag

import os

length = 2048

p, q = number.getPrime(length//2), number.getPrime(length//2)

N = p*q

e = 3

m = number.bytes_to_long(flag)

x = number.bytes_to_long(os.urandom(length//8))

c = pow(m|x, e, N)

print('N =', N);

print('e =', e);

print('c =', c);

print('m&x =', m&x);

We are also given the public key, the ciphertext and two other values.

N = 13876129555781460073002089038351520612247655754841714940325194761154811715694900213267064079029042442997358889794972854389557630367771777876508793474170741947269348292776484727853353467216624504502363412563718921205109890927597601496686803975210884730367005708579251258930365320553408690272909557812147058458101934416094961654819292033675534518433169541534918719715858981571188058387655828559632455020249603990658414972550914448303438265789951615868454921813881331283621117678174520240951067354671343645161030847894042795249824975975123293970250188757622530156083354425897120362794296499989540418235408089516991225649

e = 3

c = 6581985633799906892057438125576915919729685289065773835188688336898671475090397283236146369846971577536055404744552000913009436345090659234890289251210725630126240983696894267667325908895755610921151796076651419491871249815427670907081328324660532079703528042745484899868019846050803531065674821086527587813490634542863407667629281865859168224431930971680966013847327545587494254199639534463557869211251870726331441006052480498353072578366929904335644501242811360758566122007864009155945266316460389696089058959764212987491632905588143831831973272715981653196928234595155023233235134284082645872266135170511490429493

m&x = 947571396785487533546146461810836349016633316292485079213681708490477178328756478620234135446017364353903883460574081324427546739724

x = 15581107453382746363421172426030468550126181195076252322042322859748260918197659408344673747013982937921433767135271108413165955808652424700637809308565928462367274272294975755415573706749109706624868830430686443947948537923430882747239965780990192617072654390726447304728671150888061906213977961981340995242772304458476566590730032592047868074968609272272687908019911741096824092090512588043445300077973100189180460193467125092550001098696240395535375456357081981657552860000358049631730893603020057137233513015505547751597823505590900290756694837641762534009330797696018713622218806608741753325137365900124739257740

Let’s analyze the dimensions of these numbers.

N = 2047 bits

c = 2046 bits

m&x = 439 bits

x = 2047 bits

Observe that x also shows up in the encrypted message c = pow(m|x, e, N) and since x is way larger than the message,

we also know the first $2047 - 439 = 1608$ bits of m|x.

The problem simplifies in $(a + b)^{e}\ \bmod{N}$ also know as a stereotyped message where we know a part of the plaintenxt message a.

Also, remember that the public exponent e is 3. That’s very low! This open up a few attack vectors based on Low public exponent.

Using this paper we can get an idea of

the attacks that we could try out.

Bits of complicated math here and there, we arrive at the section 4.1 Coppersmith theorem. This will do the trick!

One of it’s use cases is to retrieve the message when there’s a low exponent and a stereotyped message.

Knowing 1608 out of 2047 bits should be good enough.

Using an already existing implementation in sage.

... # coppersmith implementation can be seen from the link above

############################################

# Test on Stereotyped Messages

##########################################

# Known values

length_N = 2047

N = 13876129555781460073002089038351520612247655754841714940325194761154811715694900213267064079029042442997358889794972854389557630367771777876508793474170741947269348292776484727853353467216624504502363412563718921205109890927597601496686803975210884730367005708579251258930365320553408690272909557812147058458101934416094961654819292033675534518433169541534918719715858981571188058387655828559632455020249603990658414972550914448303438265789951615868454921813881331283621117678174520240951067354671343645161030847894042795249824975975123293970250188757622530156083354425897120362794296499989540418235408089516991225649

ZmodN = Zmod(N);

e = 3

C = 6581985633799906892057438125576915919729685289065773835188688336898671475090397283236146369846971577536055404744552000913009436345090659234890289251210725630126240983696894267667325908895755610921151796076651419491871249815427670907081328324660532079703528042745484899868019846050803531065674821086527587813490634542863407667629281865859168224431930971680966013847327545587494254199639534463557869211251870726331441006052480498353072578366929904335644501242811360758566122007864009155945266316460389696089058959764212987491632905588143831831973272715981653196928234595155023233235134284082645872266135170511490429493

# Known part

m_and_x = 947571396785487533546146461810836349016633316292485079213681708490477178328756478620234135446017364353903883460574081324427546739724

known_x = 15581107453382746363421172426030468550126181195076252322042322859748260918197659408344673747013982937921433767135271108413165955808652424700637809308565928462367274272294975755415573706749109706624868830430686443947948537923430882747239965780990192617072654390726447304728671150888061906213977961981340995242772304458476566590730032592047868074968609272272687908019911741096824092090512588043445300077973100189180460193467125092550001098696240395535375456357081981657552860000358049631730893603020057137233513015505547751597823505590900290756694837641762534009330797696018713622218806608741753325137365900124739257740

unknown_bits = 439 # len m_and_x

known_part = (known_x >> unknown_bits) << unknown_bits # set unknown bits as 0

# Problem to equation

P.<x> = PolynomialRing(ZmodN)

pol = (known_part + x)^e - C

dd = pol.degree()

# Tweak those

beta = 1 # b = N

epsilon = beta / 7 # <= beta / 7

mm = ceil(beta**2 / (dd * epsilon)) # optimized value

tt = floor(dd * mm * ((1/beta) - 1)) # optimized value

XX = ceil(N**((beta**2/dd) - epsilon)) # optimized value

# Coppersmith

start_time = time.time()

roots = coppersmith_howgrave_univariate(pol, N, beta, mm, tt, XX)

# output

print("\n# Solutions")

print("found:", str(roots))

print("in: %s seconds " % (time.time() - start_time))

print("\n")

$ sage solve.sage

...

# Solutions

found: [1302786255172809348903083671762545816851509465261237799745282435972339495760259999870768350015069248972160348364210110655594430982141]

in: 0.05863523483276367 seconds

Now, knowing m|x, m&x and x is possible to retrieve m with only logic.

Interestingly, later we also discovered that the truth table is the same as the one for xor with 3 inputs.

from Crypto.Util import number

m_or_x = 1302786255172809348903083671762545816851509465261237799745282435972339495760259999870768350015069248972160348364210110655594430982141

m_and_x = 947571396785487533546146461810836349016633316292485079213681708490477178328756478620234135446017364353903883460574081324427546739724

x = 15581107453382746363421172426030468550126181195076252322042322859748260918197659408344673747013982937921433767135271108413165955808652424700637809308565928462367274272294975755415573706749109706624868830430686443947948537923430882747239965780990192617072654390726447304728671150888061906213977961981340995242772304458476566590730032592047868074968609272272687908019911741096824092090512588043445300077973100189180460193467125092550001098696240395535375456357081981657552860000358049631730893603020057137233513015505547751597823505590900290756694837641762534009330797696018713622218806608741753325137365900124739257740

print(number.long_to_bytes(m_and_x ^ m_or_x ^ int(bin(x)[-439:],2)))

🏁 utflag{C0u1dNt_c0m3_uP_w1tH_A_Cl3veR_f1aG_b61a2defc55f}

Sleeves

I like putting numbers up my sleeves. To make sure I can fit a lot of them, I keep the numbers small.

This challenge was solved after the end of the ctf

from challenge.eccrng import RNG

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Hash import SHA256

rng = RNG()

# I'll just test it out a few times first

print("r1 = %d" % rng.next())

print("r2 = %d" % rng.next())

r = str(rng.next())

aes_key = SHA256.new(r.encode('ascii')).digest()

cipher = AES.new(aes_key, AES.MODE_ECB)

print("ct = %s" % cipher.encrypt(b"????????????????????????????????????????").hex())

r1 = 135654478787724889653092564298229854384328195777613605080225945400441433200

r2 = 16908147529568697799168358355733986815530684189117573092268395732595358248

ct = c2c59febe8339aa2eee1c6eddb73ba0824bfe16d410ba6a2428f2f6a38123701

Seems like we have to break a PRNG…

I added some annotations in the following code to help understand the meaning of it.

from random import randint

class RNG:

def __init__(self):

# NIST P-256 curve

p = 115792089210356248762697446949407573530086143415290314195533631308867097853951

# Short weistrass curve -> y^2 = x^3 + (-3)x + b

# with a = -3

# with b = 41058363725152142129326129780047268409114441015993725554835256314039467401291

b = 0x5ac635d8aa3a93e7b3ebbd55769886bc651d06b0cc53b0f63bce3c3e27d2604b

self.curve = EllipticCurve(GF(p), [-3,b])

self.P = self.curve.lift_x(110498562485703529190272711232043142138878635567672718436939544261168672750412)

self.Q = self.curve.lift_x(67399507399944999831532913043433949950487143475898523797536613673733894036166)

self.state = randint(1, 2**256)

def next(self):

# this is the discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP), can't find self.state knowing sP and self.P

sP = self.state * self.P

r = Integer(sP[0])

self.state = Integer( (r * self.P)[0] )

rQ = r * self.Q

return Integer(rQ[0])>>8

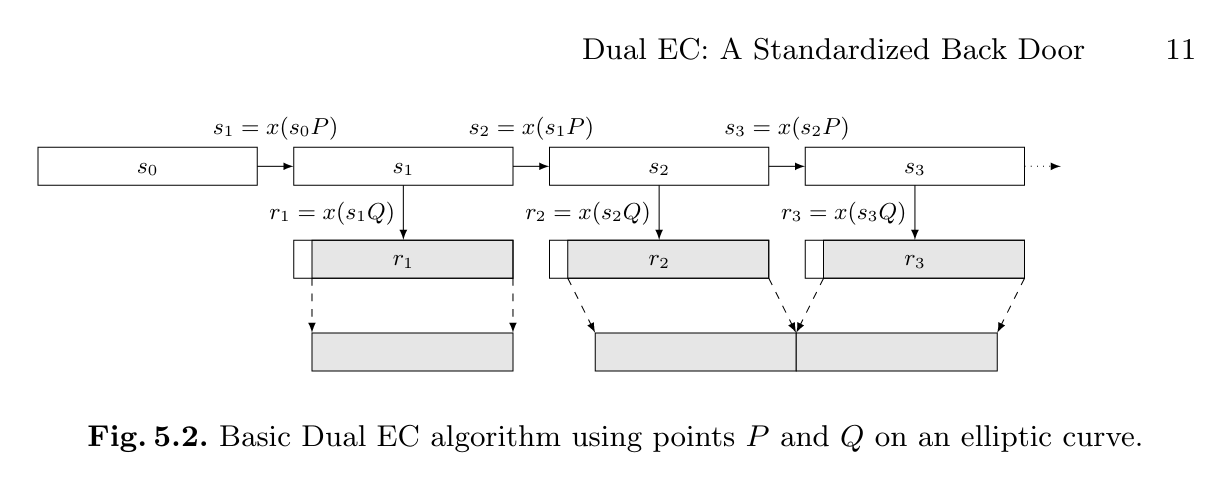

The inner workings are not that strange, two points on a curve P, Q and an initial random state.

Each round P is used to change the inner state and Q is used to generate a pseudo-random number.

The initial state can’t be bruteforced in a reasonable amount of time and for whom might be new to ECs, multiplication correspond

to the discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP) and therefore can’t be easily reversed.

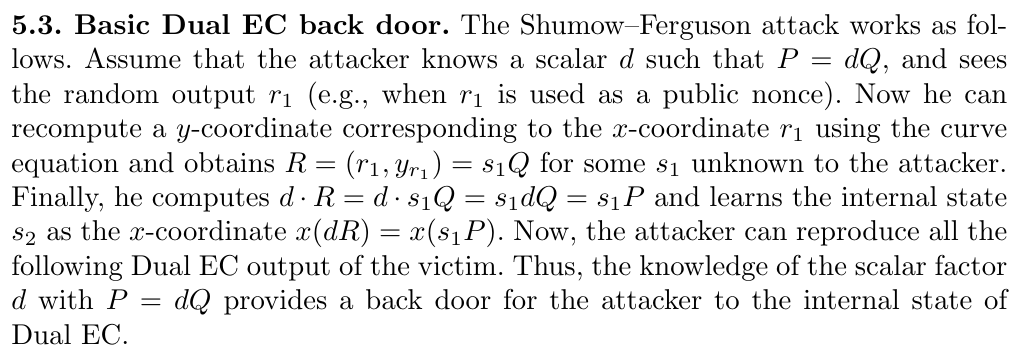

Searching for this type or PRNG we found a paper on the backdoored implementation by the NSA (Dual_EC_DRBG).

Looks like our implementation. Let’s analyze the backdoor.

For this attack to work a scalar d such that $P = dQ$ is needed. Sage can help us with it’s internal function discrete_log()

sage: p = 115792089210356248762697446949407573530086143415290314195533631308867097853951

sage: b = 0x5ac635d8aa3a93e7b3ebbd55769886bc651d06b0cc53b0f63bce3c3e27d2604b

sage: curve = EllipticCurve(GF(p), [-3,b])

sage: P = curve.lift_x(110498562485703529190272711232043142138878635567672718436939544261168672750412)

sage: Q = curve.lift_x(67399507399944999831532913043433949950487143475898523797536613673733894036166)

sage: # P = dQ

sage: Q.discrete_log(P)

173

In a few seconds sage was able to recover it, great!

As the last step, looking back at the challenge implementation, the next() function cuts off the last 8 bits of the generated number. That is not going to be a problem, knowing what to except on the right case, they can be bruteforced.

from pwn import *

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Hash import SHA256

# ciphertext

ct = unhex("c2c59febe8339aa2eee1c6eddb73ba0824bfe16d410ba6a2428f2f6a38123701")

# NIST P-256 curve

p = 115792089210356248762697446949407573530086143415290314195533631308867097853951

b = 0x5ac635d8aa3a93e7b3ebbd55769886bc651d06b0cc53b0f63bce3c3e27d2604b

curve = EllipticCurve(GF(p), [-3,b])

P = curve.lift_x(110498562485703529190272711232043142138878635567672718436939544261168672750412)

Q = curve.lift_x(67399507399944999831532913043433949950487143475898523797536613673733894036166)

# P = dQ

d = Q.discrete_log(P)

# Leaked internal random state

r2 = 16908147529568697799168358355733986815530684189117573092268395732595358248

def get_random(state):

sP = state * P

r = Integer(sP[0])

rQ = r * Q

return Integer(rQ[0])>>8

def validate(key):

aes_key = SHA256.new(key.encode('ascii')).digest()

cipher = AES.new(aes_key, AES.MODE_ECB)

msg = cipher.decrypt(ct)

if b"utflag" in msg:

log.info(msg)

return True

return False

# Bruteforce last 8 bits of internal state

_log = log.progress('bruteforce')

r_x_guess = r2 << 8

for i in range(256):

try:

R = curve.lift_x(r_x_guess)

next_state_guess = Integer((d * R)[0])

_log.status(f"{i}")

next_random = get_random(next_state_guess)

if validate(str(next_random)):

_log.success(f"state = {next_state_guess}")

break

except ValueError:

pass

r_x_guess += 1

🏁 utflag{numbers_up_my_sl33v3_l0l}

Web

Fastfox

Help me show Bob how slow his browser is!

http://web1.utctf.live:8124/

After navigating to the challenge’s link, we are presented with a page that contains a text area and a submit button. There is some example code in the text area:

console.log('hello world');

and a paragraph that reads:

Test Bob's Browser!

Bob uses a really old version of Firefox,

so I figured I'd show him how so slow it is

by letting anyone submit JavaScript for him

to run. Just put your JavaScript in below,

and Bob will run it in his outdated browser.

This suggests us that we need to do some sort of RCE or LFI by making Bob’s browser run some javascript code that will get us the flag.

The first thing I did was to try run the example code. After clicking the submit button, a page pops up, reading:

output:

hello world

My first thought was to explore which things I could log to the page, starting from the this variable, if it was defined.

After submitting:

console.log(this);

The output says:

output:

[object global]

which tells me that I have access to the variable. This, however, doesn’t tell me much about it. Since it is a Javascript Object, I know that there is a way to get all its keys, which could be some defined functions. I submitted this code:

console.log(Object.keys(this));

and got a very big output, which surprised me a little. Here is a portion of it:

output:

clone,version,options [...] nestedShell

I looked through the listed keys for a while, until my attention was caught by the nestedShell function. I thought that I could maybe use it to open a shell and read the flag. I tried using the command like this:

nestedShell("/flag.txt");

but I got an error:

errors:

Error: can't open /flag.txt: No such file or directory.

493196937370842568.js:1:13 Error: error executing nested JS shell

Stack:

@493196937370842568.js:1:13

Which prompted me to look on the Internet for some documentation.

I eventually stumbled across this website

which contained some commands of the JavaScript shell which is a command-line implementation of the one included in the Firefox browser.

Looking through these docs, I found about the command read() which allows you to read the contents of a local file.

I then submitted the following code:

console.log(read("flag.txt"));

and the output contained the flag!

NOTE: While writing this, I discovered another solution, that I missed by a hair. This is to just submit a slightly different version of the nestedShell command:

nestedShell("flag.txt");

which is the same but without the “/” at the start. This produces the following error:

errors:

flag.txt:1:6 SyntaxError: unexpected token: '{':

flag.txt:1:6 utflag{REDACTED}

flag.txt:1:6 ......^

1489857498705983299.js:1:1 Error: error executing nested JS shell

Stack:

@1489857498705983299.js:1:1

which just contained the flag!

🏁 utflag{d1d_y0u_us3_a_j1t_bug_0r_nah}

Networking

Be My Guest

Can you share some secrets about this box?

nmap is allowed for this problem. However, you may only target ‘misc.utctf.live port 8881 & 8882’. Thank you.

Such an explicit scanning permission needs to be acted upon, and while we’re at it let’s enable some version detection too:

nmap -sV -T4 -p 8881-8882 misc.utctf.live

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

8881/tcp open netbios-ssn Samba smbd 4.6.2

8882/tcp open netbios-ssn Samba smbd 4.6.2

Samba shares in a challenge with “guest” in its name? Anonymous credentials are worth try:

smbclient -U anonymous%anonymous -p 8881 -L misc.utctf.live

Sharename Type Comment

--------- ---- -------

guest Disk Look, but don't touch please.

IPC$ IPC IPC Service (Samba Server)

Let’s browse the share’s contents:

smbclient -p 8881 -U anonymous%anonymous \\\\misc.utctf.live\\guest

smb: \> ls

. D 0 Fri Mar 12 07:45:26 2021

.. D 0 Fri Mar 12 23:44:53 2021

flag.txt N 30 Fri Mar 12 07:45:26 2021

smb: \> get flag.txt

getting file \flag.txt of size 30 as flag.txt (0,1 KiloBytes/sec) (average 0,1 KiloBytes/sec)

Nice :)

🏁 utflag{gu3st_p4ss_4_3v3ry0n3}

Hack Bob’s Box

Hack Bob’s box!

nmap is allowed for this problem only. However, you may only target utctf.live:8121 and utctf.live:8122 with nmap.

Like before, let’s poke at the thing and try some slightly more aggressive version detection:

nmap -sC -sV -T4 -p 8121-8122 misc.utctf.live

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

8121/tcp open ftp Pure-FTPd

| ftp-anon: Anonymous FTP login allowed (FTP code 230)

|\_Can't get directory listing: PASV IP 172.19.0.2 is not the same as 3.236.87.2

8122/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.6p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.3 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 31:84:d1:43:41:53:48:71:50:6a:91:51:13:a9:97:88 (RSA)

| 256 48:00:d0:e3:0f:53:d5:d2:42:0a:be:0d:69:d1:5f:ba (ECDSA)

|\_ 256 99:0f:41:82:b1:ce:3b:06:6c:ab:55:c5:46:e7:c2:a7 (ED25519)

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux\_kernel

After a few tries with lftp and ftp, it’s confirmed that the FTP server is returning an unroutable (internal) IP address when enabling passive mode. Active mode won’t get us anywhere and trying to manually override the PORT command gets ignored by the server, which always returns a random port on 172.19.0.2.

At this point my hypothesis was that, since the OpenSSH server version was quite old, maybe some known CVE could be used to exploit it and get access to the internal network. Then we could tap into the FTP server’s passive mode session and dump the received data. After a lot of fiddling, out of the blue the FTP server actually started behaving correctly and let us in with anonymous credentials. Maybe it was misconfigured at the start of the CTF and someone fixed it later on? Anyway:

lftp anonymous:anonymous@misc.utctf.live:8121

lftp anonymous@misc.utctf.live:/> ls

drwxr-xr-x 1 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 ..

drwxr-xr-x 3 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 .mozilla

drwxr-xr-x 2 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 .ssh

drwxr-xr-x 2 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 docs

drwxr-xr-x 2 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 favs

lftp anonymous@misc.utctf.live:/> ls .ssh

drwxr-xr-x 2 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 0 0 4096 Mar 12 18:53 ..

-rw-rw-r-- 1 0 0 0 Mar 12 06:45 authorized_keys

-rw-rw-r-- 1 0 0 2622 Mar 12 06:45 id_rsa

-rw-rw-r-- 1 0 0 587 Mar 12 06:45 id_rsa.pub

-rw-rw-r-- 1 0 0 0 Mar 12 06:45 known_hosts

An SSH key is readable, but since the authorized_keys file is empty we can safely assume that it can’t be used to log in. Too bad, what else is in here? It seems that .mozilla/firefox/yu85tipn.bob/ contains Bob’s Firefox profile, let’s pull it down and inspect it.

lftp anonymous@misc.utctf.live:/> mirror .mozilla/firefox/yu85tipn.bob

Not knowing if the contents of the profile are safe, I chose to run it through firefed instead. No extensions, no relevant bookmarks, some tracking cookies, no saved logins… but some interesting history! As a bonus, it seems that Bob is interested in either animals or Nintendo emulators 🐬

firefed -p yu85tipn.bob visits

#...

2021-03-02 18:20:55 http://bobsite.com/login?user=bob&pass=i-l0v3-d0lph1n5

Aha! SSL might protect your queries (well, not in this case…), but it can’t save you from the dreaded browser history.

sshpass -p "i-l0v3-d0lph1n5" ssh -p 8122 bob@misc.utctf.live

bob@ab405b7be269:~$

Let’s abuse the server’s resources for a moment since we’re lazy and don’t want to poke around too much:

bob@ab405b7be269:~$ find / -type f -iname "*flag*" 2>/dev/null

#...

/flag.txt

🏁 utflag{red_teams_are_just_glorified_password_managers}

Reverse

Recur

I found this binary that is supposed to print flags.

It doesn’t seem to work properly though…

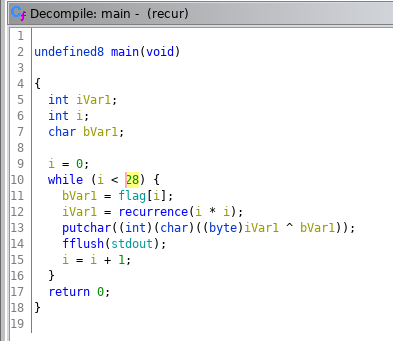

In this challenge we are given the ELF 64-bit file “recur”. If we execute the file it print “utflag{“ and then unfortunately it freezes. Let’s try to take a look at the decompiled code obtained with Ghidra in order to understand the problem:

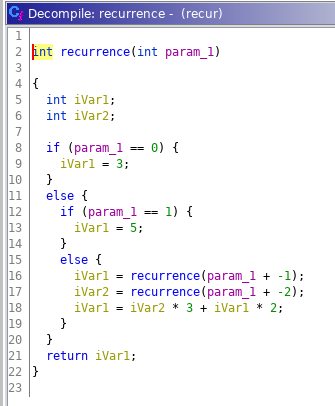

This the main of the program. We can see that is executed only a cycle of 28 iteractions, in which the flag, located in the .data section of the file, is “decrypted” with a function named recurrence followed by a XOR. Let’s see what this function consists of:

The function appears to be correct in the syntax, so problably the program freezes because the recurrence it’s too complex to compute in terms of numbers dimension and recursive calls. Maybe we can try to optimize the code of the recurrence so that it ends and we get our flag. Firstly we can notice that the only part of the value returned by the recurrence that we are going to use is one byte; so we can avoid complex calculations considering only one byte of that value.

Then we can implement a way to store results that we already calculated. The recursive calls from recurrence(n) are indeed of the type recurrence(n-1) and recurrence(n-2), so the same functions are called a lot of times during the execution. Let’s try to rewrite the recurrence function with these optimizations in python:

def recurrence(x, table):

if table[x] != -1:

return table[x]

elif x == 0:

v1 = 3

elif x == 1:

v1 = 5

else:

v1 = recurrence(x - 1, table) & 255

v2 = recurrence(x - 2, table) & 255

v1 = (int(v2) * 3 + int(v1) * 2) & 255

# print(v1)

if table[x] == -1:

table[x] = v1

return v1

res = []

table = [-1] * 28 * 28

flag = [0x76, 0x71, 0xc5, 0xa9, 0xe2, 0x22, 0xd8, 0xb5, 0x73, 0xf1, 0x92, 0x28, 0xb2, 0xbf, 0x90, 0x5a, 0x76, 0x77,

0xfc, 0xa6, 0xb3, 0x21, 0x90, 0xda, 0x6f, 0xb5, 0xcf, 0x38] #taken from .data section of the file

for i in range(28):

res.append(recurrence(i * i, table))

for i in range(28):

print(chr(res[i] ^ flag[i]), end='')

We added an and mask (& 255) to consider only one byte and a list (table) with the purpose of storing known results. With these changes the recurrence ends without problems and we obtain the flag!

🏁 utflag{0pt1m1z3_ur_c0d3_l0l}

Peeb Poob

Computers usually go beep boop, but I found this weird computer that goes peeb poob.

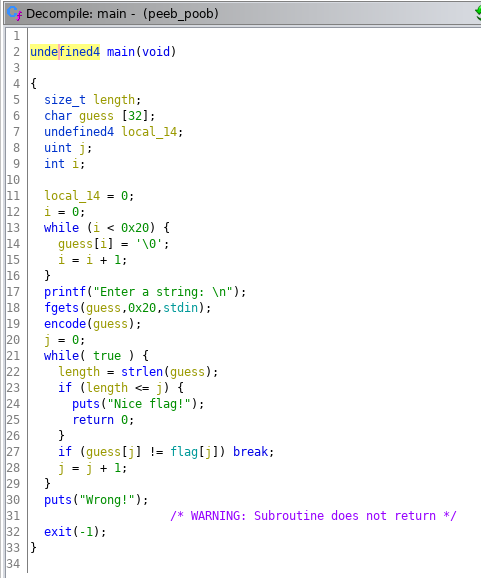

This time another ELF file, “peeb_poob” that seems to be not executable on x86-64 architectures. The only useful thing we can do is to take a look at the decompiled code in Ghidra.

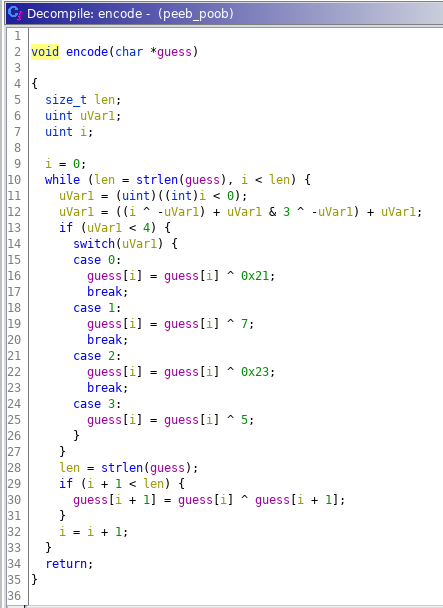

The main appears to be simple: the user can enter a string as input, which is firstly encoded and then compared char by char with a group of bytes stored in the .data section. So basically we have the encoded flag and the function used for the encoding.

One way to solve the problem is to understand how the encoding function works and based on that to derive the flag. But in a situation like this my lazy brain can only thinks about one thing: bruteforce.

I copied the encode(guess) function in python and I checked that the encoding of “utflag{“ corresponded to the bytes stored in the program. Perfect match! Then I built the flag starting from “utflag{“ and bruteforcing it char by char. Not really elegant but certainly functional.

import string

def encode(string):

length = len(string)

uVar1 = 0

i = 0

while i < length:

uVar1 = (i < 0)

uVar1 = ((i ^ -uVar1) + uVar1 & 3 ^ -uVar1) + uVar1

if uVar1 < 4:

if uVar1 == 0:

string[i] = chr(ord(string[i]) ^ 0x21)

if uVar1 == 1:

string[i] = chr(ord(string[i]) ^ 7)

if uVar1 == 2:

string[i] = chr(ord(string[i]) ^ 0x23)

if uVar1 == 3:

string[i] = chr(ord(string[i]) ^ 5)

if i + 1 < length:

string[i + 1] = chr(ord(string[i]) ^ ord(string[i + 1]))

i = i + 1

return string

x = ['u', 't', 'f', 'l', 'a', 'g', '{']

enc = [0x54, 0x27, 0x62, 0x0b, 0x4b, 0x2b, 0x73, 0x14, 0x06, 0x32, 0x61, 0x3b, 0x78, 0x4f, 0x5c, 0x29, 0x57, 0x20, 0x30,

0x06, 0x45, 0x1d, 0x4e, 0x7b, 0x6a, 0x0f, 0x51, 0x5e, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00]

for k in range(20):

for i in string.printable:

y = x.copy()

y.append(i)

y = encode(y)

if y[7 + k] == chr(enc[7 + k]):

x.append(i)

print("".join(x))

break

🏁 utflag{b33p_b00p_p33b_p00b}

Forensics

SHIFT

I just tried to download this flag, but it looks like the image got messed up in transit…

This challenge was retrospectively quite funny: the official solution involves Python, PIL, numpy, some trial end error… But some really basic GIMP knowledge would have served you quite well too.

🏁 utflag{not_when_i_shift_into_maximum_overdrive}

Doubly Deleted Data

We got a copy of an elusive hacker’s home partition and gave it to someone back in HQ to analyze for us. We think the hacker deleted the file with the flag, but before our agent could find it, they accidentally deleted the copy of the partition! Now we’ll never know what that flag was. :(

In this challenge, we have to inspect a compressed image file, flash_drive.img.gz. I started by decompressing it with:

$ gunzip flash_drive.img.gz

After unzipping, I ran the command:

$ strings flash_drive.img

and I looked through the output from the bottom-up. After a couple seconds of scrolling up, I found a list of recently ran commands, which included the flag!

[...]

mkdir secret_hacker_stuff

cd secret_hacker_stuff/

nano flag.txt

echo "utflag{REDACTED}" > real_flag.txt

rm real_flag.txt

[...]

🏁 utflag{d@t@_never_dis@ppe@rs}

Sandwiched

I got this super confidential document that is supposed to have secret information about the flag, but there’s nothing useful in the PDF!

We get a secret.pdf file. If opened, it shows the text “No flag here”. This is very suspicious. We used binwalk to inspect the pdf file, with this command:

$ binwalk secret.pdf

which gives this output:

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 PDF document, version: "1.5"

71 0x47 Zlib compressed data, default compression

290 0x122 Zlib compressed data, default compression

6252 0x186C Zlib compressed data, default compression

7824 0x1E90 JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01

37768 0x9388 PDF document, version: "1.5"

37839 0x93CF Zlib compressed data, default compression

38058 0x94AA Zlib compressed data, default compression

[...]

We can see that there are mostly PDF and Zlib compressed files, but there is one file that stands out. Starting from offset: 7824 binwalk found a JPEG file, which might contain the flag. To extract it, we can calculate the length of the JPEG file by taking the difference between its offset and the offset of the next file:

$ 37768 - 7824 = 29944 $

And so we can extract the JPEG file by using binwalk:

$ binwalk secret.pdf -o 7824 -l 29944 --dd=".*"

Upon inspecting the JPEG file, we see that it does in fact contain the flag!

🏁 utflag{file_sandwich_artist}

Misc

Emoji Encryption

I came up with this rad new encryption. Bet no one can break it

☂️🦃🔥🦁🍎🎸{🐘🥭🧅🤹🧊☀️_💣🐘_🌋🐘🌈☀️🍎🦃🧊🦁🐘}

We are given a series of emojis, curly brackets and underscores. Those are aranged in a way such that it’s pretty easy to recognize a flag disguised as a sequence of emojis. It’s also intuitive to recognize that every letter of the flag is encoded with an emoji that rapresents an animal/object which has as first letter of its name as the above-mentioned letter. In order to decrypt the flag, the only thing we have to do is to replace every emoji with the first letter of its name (for clarity’s sake I’ve substituted every emoji with it’s name and capitalized and bolded the first letter):

UmbrellaTurkeyFireLionAppleGuitar{ElephantMangoOnioJugglerIceSun_BombElephant_VolcanoElephantRainbowSunAppleTurkeyIceLionElephant}

🏁 utflag{emojis_be_versatile}