Less magic, more introspectability

Nowadays, given an unlimited combination of budget, time and accumulable technical debt it’s far too easy to just spin up a humongous Kubernetes cluster on one of the plethora of managed services available, write a couple of lines of YAML and declare to be done with your infra. But anyone that has experimented with this trope knows that making such a system reliable, inspectable, and especially being able to quickly recover it in case things go south is an entirely different matter.

Since we didn’t expect a massive influx of users for this first edition of the DanteCTF - about 100 individuals registered before the start of the event, partly due to it being structured more as an introduction to CTFs rather than a fully featured competition - the technical budget ended up being made of a single AWS EC2 instance. For the sake of performance and maintainability we decided to try and reduce the operational overhead to the bare minimum but without losing important observability and resource managament capabilities.

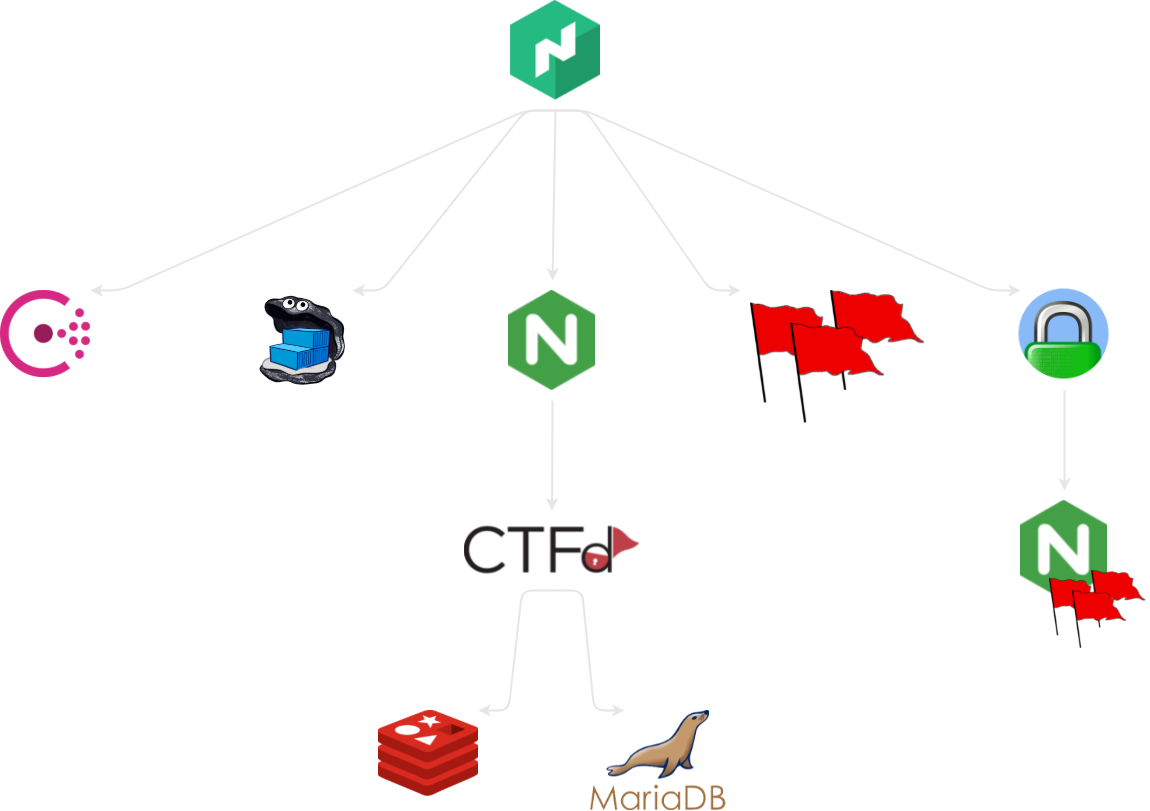

Topology

Hey, what did you expect? We told you we wanted to keep it simple :)

Everything ran on a t2.large (2 vCPUs, 8GiB RAM) EC2 instance, even though we’ll highlight later on how we could have gone for a t2.medium after some careful tuning. Downscaling even more could have been possible, but losing core parallelism could have caused minor annoyances down the line.

Network Security

A set of two firewalls stood between the Big Evil Internet and our VM: AWS’s own Security Groups did the heavy lifting by allowing traffic only on our public facing ports, while ACLs and IP whitelists for administrative interfaces were managed directly on the machine through UFW (namely iptables, more on that later), geoblocking and WAFs.

Software

Even though CTFd was the obvious choice for the competition’s management platform and the LetsEncrypt & CertBot combination handled issuing SSL certificates, we stil needed to find a task manager/orchestrator that balanced our needs of operational security (i.e.: isolating and constraining challenges) with a minimal resources footprint.

Complex multi-host building blocks like K8S were already right out of the question: having had prior experiences with bringing them up on a single node confirmed that we didn’t have the time and willingness to babysit such fragile solutions throughout the event, let alone implement decent disaster recovery procedures (because when something like single-node K8S breaks, it breaks hard).

Something that ticked all our boxes was Nomad. HashiCorp’s products are usually enjoyable to use and don’t require extensive knowledge to have an MVP up and running, so we dived into it and in a matter of hours a first crude setup of CTFd plus a single challenge was indeed brought up with just the right amount of research.

Usually there are pretty solid reasons for the official docs of something to tell you that you need at least N hosts with X, Y and Z capabilities, but we were pleasantly surprised by how… uneventful consciously going against such recommendations has been with Nomad. By running on a single host we were basically only giving up horizontal scalability, and there have been no memorable hiccups during configuration. Try to run some half-serious distro of K8S in this setup and let me know if you didn’t get stuck at least once in some tricky situation where internal services got deadlocked due to not expecting to be running onto the same host.

The obvious downside to every single-node approach is reliability: if that machine goes down, so do your services. We were pretty confident in our strategy though, for a couple of reasons: first of all, if EC2 suffers serious outages (*cough* not necessarily reported by their status dashboard *cough*) it usually means that there will be bigger problems in the IT world than a small CTF not being playable; incremental backups were easy to do and, even if we were forced to restart from stratch, our automated deployment pipelines enabled us to be back up and running in under 10 minutes (even half of that if we consider that not everything would have had to be rebuilt, local caches would do their job).

Architecture

From left to right, top to bottom, Nomad was overseeing and coordinating these services:

Consul

Consul was needed for service discovery and health checking. We could have also stored some of the challenges’ config data in its embedded key-value store, but we chose not to go down that rabbit hole in favor of Nomad’s injectable config templates since they were more than capable enough for our purposes.

Running Consul directly from Nomad (HashiCeption!) was, again, surprisingly easy due to Nomad being able to handle different types of workloads: the latest binary release was downloaded from the official repository, ran as an isolated process, and managed just like SystemD would do with a standard service. Nomad itself has no hard dependency on Consul in this configuration since clustering is disabled and it doesn’t have to discover any other node. I thought this would be one of the most delicate parts of the setup, but it turned out to be a pretty comfy and self-healing way to run Consul after all. Service resolution via DNS still required some hackery due to hardcoded defaults in systemd-resolved, but more on that later.

Docker Registry

A standard Docker registry used internally to store customized CTFd and challenges’ images, built remotely and pushed up during the initial configuration or if live patching was found to be necessary. TLS termination is done by the service itself with the aforementioned certificates.

CTFd

The CTFd job was composed by a couple of moving parts:

- An NGINX reverse proxy whose tasks were handling TLS termination, handling HTTP to HTTPS upgrades, and filtering traffic to/from CTFd.

- The actual CTFd instance, including custom themes and plugins.

- A Redis instance to support CTFd as cache, as per the official docs.

- A MariaDB instance to store CTFd’s data, as per the official docs. The VM’s disk performance hadn’t been tested thoroughly and thus we chose not to rely on SQLite, even though it would have most probably handled our expected traffic just fine.

Unproxied challenges

Some challenges were served directly over the network since they were capable of handling their own traffic and/or weren’t HTTP-based. Some of them were run as Docker containers since they needed bundled assets or dependencies, while others were pure binaries that could be run directly by Nomad using the Linux kernel’s own namespacing facilities.

Proxied challenges

Some challenges, especially the ones in the Web category, weren’t built to be directly exposed over the web or it was preferable for them not to handle TLS termination by themselves - especially for ease of development. To avoid having to setup a whole new NGINX instance just for these basic additions, we chose to use the simpler Caddy server with just a couple of lines of configuration, whose defaults include many features that were desirable in this scenario.

In the end all web challenges were served by the same NGINX + PHP container, secured behind said Caddy reverse proxy. If the number of challenges or their complexity was considerably higher we would have probably merged the two proxies to get rid of some overhead, but in this case the benefits of the separation of concerns and configurations outweighted the theoretical performance hits.

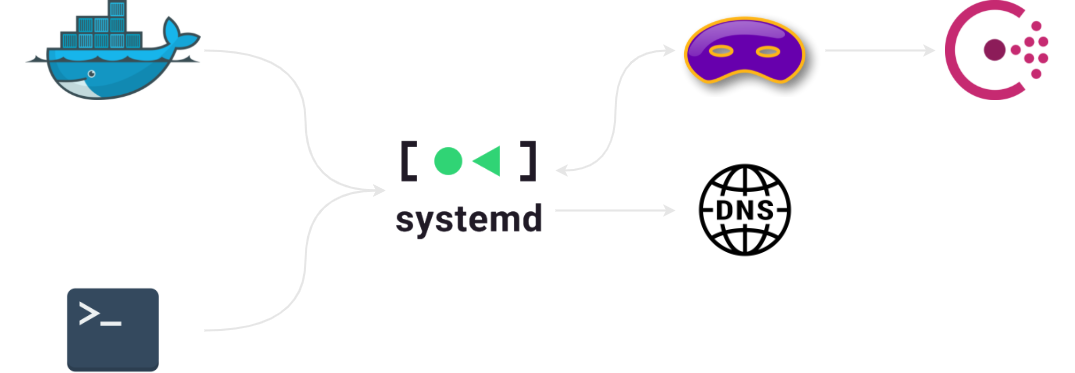

Service discovery

Service discovery through DNS records is an awesome feature of Consul, but this time a bit of hackery was required to make it work with our setup: long story short, systemd-resolved (Ubuntu’s default DNS resolver since 18.04) only supports forwarding DNS queries to upstream servers listening on port 53 and thus it couldn’t be pointed directly to Consul.

The workaround consisted in throwing dnsmasq in the loop and binding it to Docker’s interface to avoid port conflicts with systemd-resolved; the latter routed all requests ending in .consul to the former, which in turn would query Consul and eventually fall back to systemd-resolved if no results turned up. Queries would be then forwarded through the network’s usual DNS resolvers by systemd-resolved.

This was the only occurrence so far where being constrained to a single EC2 instance annoyed us to some degree, mostly because I didn’t feel this solution was robust enough to be quickly troubleshooted in case of unexpected problems during the event. In a bigger setup all of this mess would most probably have been consolidated into a single dedicated DNS server, either through a managed service (AWS Route 53?) or a properly configured dnsmasq instance.

Docker footguns

If you plan to use UFW to manage your firewall (that is to say iptables rules), take notice that Docker’s port bindings happily insert themselves in the rules chain higher up than UFW’s, bypassing the latter’s configuration altogether. A quick search for “docker ufw” shows that this is not a trap operators rarely fall into, hypothesis also corroborated by these two recent HackerNews submissions. In the end we chose to apply a workaround based on chaifeng’s idea.

<rant>

The Docker/Moby team has known of the issue since 2014 (see 1, 2, 3), but to me it seems that it’s one of those situations where everyone insists on shifting the blame instead of actually trying to fix the problem - or at least try to make people aware of it before damage is done. Personally, I find that a 7-lines paragraph in the official Docker docs is nowhere near enough to warn operators about this potentially critical security issue (no matter how easily detectable it is), especially when said page of the docs doesn’t even even come up within the first search results for the keywords mentioned above; when multiple hacky user-developed fixes get ranked higher than your own docs, maybe some actions should be taken.

</rant>

Considerations

Reproducibility

We wanted to be able to tear this environment down and bring it back up relatively fast to aid with testing and temporary setups during development, so we rigorously kept an Ansible playbook in sync from the start. It ended up being a relatively small feat at ~400 lines of YAML tasks, Bash helper scripts and HCL job definitions that, despite having taken quite some time to get right under all possible initial stages, gave us the confidence of having an easily reproducible and maintainable setup, in a container-like immutable fashion; no need to manually upgrade single components one after the other and check for temporary conflicts when you can reapply all your changes at once.

Bottom line

In the end the event turned out pretty successfully and our architecture proved itself stable enough to withstand a much bigger load so, unless some newer and shinier tech comes out, I think next year’s DanteCTF will be based on a very similar stack with a few performance and monitoring tweaks baked in. Something that I’ll look into, for example, will most probably be adding Prometheus metrics directly into challenges when possible and generally overhauling our logs and submissions monitoring pipelines. Oh, and some kind of bot for the Discord support server since manually announcing first bloods and time left is… kind of a pain.